At First

As a part-time user, I am aware that SMPL (A Skinned Multi-Person Linear Model) is an effective parametric model that can describe the shape of a skinned human with relatively small parameters. It was first published in 2015, and there have been many extensions to it since.

However, as I was working on human rendering, it became essential for me to have a fundamental understanding of how it works: how we can build a posed human mesh with a unique shape from a template mesh, what steps are involved, and most importantly, how this process differs from character animation in 3D software like Maya or Blender. These are the topics we will be discussing here.

BTW, I just found a solid wiki on SMPL models (Meshcapade Wiki). It seems very informative and complete, and I think it could come in handy when I need to check something or refresh my memory.

SMPL Basics

Before getting into all the fancy SMPL-X, SMPL-H, SMAL… We do need to understand what could the basic SMPL model offer. According to the original paper, the most important equation is this:

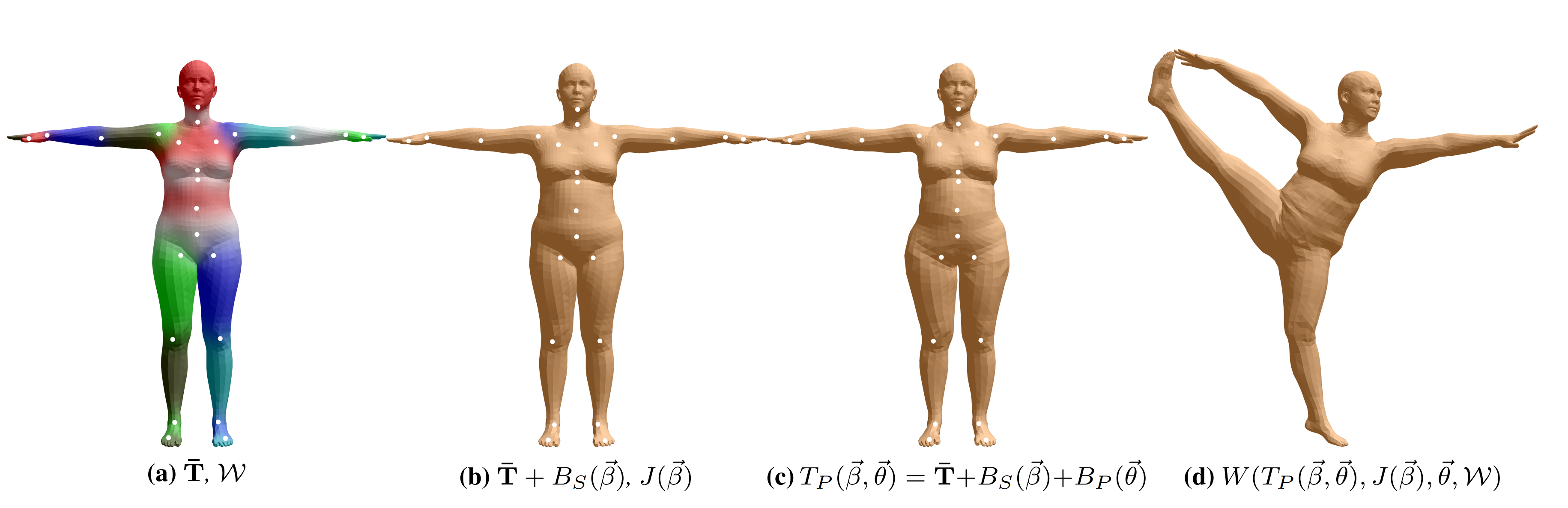

So according to this figure, 4 steps are taken. And Let’s take it step by step.

Recap: LBS

So, in case you forget, let’s do a quick recap on LBS. In the sense of LBS on mesh, given a vertex position $v_{j}$, we want to deform it to $v_{j}^{‘}$, using the blending weights $w_{ij}$ , every bone’s translation matrix $T_{i}$ , and also the vertex position $v_j^{i}$ in that bone’s coordinate frame. Formally, it could be written as:

\[v_{j}^{'} = \sum_{i}w_{ij}T_{i}v_j^{i}\]So in hindsight, this is just to blend every bone’s transformation with a weight, that is assigned by every bone $i$ to every vertex $v_j$.

This is kind of naive though, given the fact that 2 opposite transformation could easily result in a degraded point, which is called the ‘candy wrap’ problem. One can use dual quaternion (DQBS), to eliminate this problem. But this kind of blending could also result in over smoothness or some other artifacts, so it’s not perfect either. For details, you can refer to Prof. Libin Liu’s excellent course on character animation: Skinning.

Step 1. Template Mesh & Blending Weights

The mesh template and the blending weight can be seen as $\overline{\mathbf{T}} \in \mathbb{R}^{3N}$ and $\mathcal{W} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times K}$, respectively. Sometimes I mix up the blending weights with the skinning weights, we might have to clarify a bit here. This $\mathcal{W}$ is the blending weight, which is used to blend K transformations from K joints together, and produce a deformation for all $N$ vertices. Formally, it is used in a standard Blend Skinning function (LBS or DQBS), can be formulated as:

\[W\left(T_P(\vec{\beta}, \vec{\theta}), J(\vec{\beta}), \vec{\theta}, \mathcal{W}\right)\]We know that $\vec{\beta}, \vec{\theta}$ are input shape and pose parameters, respectively. How could us get the parameters needed for LBS, namely $T_P(\vec{\beta}, \vec{\theta})$ and $J(\vec{\beta})$? The former one could be written as:

\[T_P(\vec{\beta}, \vec{\theta}) =\overline{\mathbf{T}}+B_S(\vec{\beta})+B_P(\vec{\theta})\]So it’s basically template mesh + shape blend offsets + pose blend offsets, which leads us to:

Step 2. Shape Blend Shapes($B_S(\vec{\beta})$)

So from the previous step, we have the template mesh. Now given the shape parameter vector $\vec{\beta}$, we can obtain the shape induced offsets by:

\[B_S(\vec{\beta} ; \mathcal{S})=\sum_{n=1}^{|\vec{\beta}|} \beta_n \mathbf{S}_n\]In which the $\mathbf{S}_n \in \mathbb{R}^{3 N}$ represent orthonormal principal components, which are determined by PCA training. This corresponds to the shapedirs that we use in SMPL codes. Specifically, we can implement this process by:

shape_blend_offsets = shapedirs@betas

The other blending is:

Step 3. Pose Blend Shape($B_P(\vec{\theta})$)

This is a bit more complicated. To start off, we now gives a general view of pose shape blend:

\[B_P(\vec{\theta} ; \mathcal{P})=\sum_{n=1}^{9 K}\left(R_n(\vec{\theta})-R_n\left(\vec{\theta}^*\right)\right) \mathbf{P}_n,\]Now let’s break down this formation. We denote as $R: \mathbb{R}^{|\vec{\theta}|} \mapsto \mathbb{R}^{9 K}$ a function that maps a pose vector $\vec{\theta}$ to a vector of concatenated part relative rotation matrices, $\exp (\vec{\omega})$. Given that our rig has 23 joints, $R(\vec{\theta})$ is a vector of length 23 x 9 = 207.

There are few clarifications to make:

- The mapping function is actually just a rodriguez formula, which should be trivia. But I guess they want to make the theta vector of a smaller shape to demonstrate the power of PCA, so you kind of have to use this so-called map function.

- Here $\mathcal{P}=\left[\mathbf{P}1, \ldots, \mathbf{P}{9 K}\right] \in \mathbb{R}^{3 N \times 9 K}$ , aka. posedirs are learned using PCA.

Well these are all kind of boring, lets show some code. Let’s try to implement this process with numpy.

def blend_pose(posedirs, theta, theta_star):

'''

args:

posedirs: (P in equation), with a shape of 3N x 9K, for each joint it has 9 values.

theta: current pose

theta_star: rest pose

'''

pose_diff_vec = (Rodriguez(theta) - Rodriguez(theta_star)).ravel() # a vector of length 9K

blend_pose_offset = posedirs @ pose_diff_vec

return blend_pose_offset

BTW, I do think a blog about all forms of rotations, including rodriguez formula, should be a future post.

Step 4. Joint Locations

Now we already have the deformed mesh. In order to do the final LBS, we need to regress the joint locations too. If we look at python code, it is more than simple:

J = J_regressor@v_deformed

This J_regressor is also learned.

Step 5. Skinning

As mentioned in step 1, LBS is next. But, up until this point, I still have some questions.

Are the weights the same for every $\vec{\theta}$ , $\vec{\beta}$?

For SMPL model, sadly, the answer is yes. ChatGPT justfies this by saying that the weights are supposed to be a linear approximation of the influence by different joints in the kinematic tree, not the detailed deforms; and it also mentions that this is for efficiency and flexibility concern. Actually the weights are precomputed and learned through training.

If we already have joint transformations as in $\vec{\theta}$ , why would we not have an accurate human keypoints?

Well, actually, most methods that estimate SMPL parameters, would prefer estimating $\vec{\theta}$, instead of estimating 3D pose. Actually, ChatGPT gives me some reasons, which I thought kind make sense:

- Compact representation: The relative rotations allow for a compact representation of the pose, as opposed to estimating the 3D joint locations or other pose representations that might have more parameters or require additional constraints.

- Flexibility: Estimating the pose vector directly allows for a more flexible and expressive representation that can capture a wide range of human poses, while still being easy to work with in terms of optimization or learning.

- Robustness: Directly estimating the pose vector can be more robust to errors than estimating 3D joint locations, as small errors in the relative rotations can still lead to visually plausible results.

We might try dig into some more SMPL estimation / motion capture methods in the future.

How do we implement the LBS process?

Obviously, almost all the vertices are influenced by 2-4 joints, so we do not need to calculate 24 rotations for every vertice. Instead, a tree structure is often used to implement LBS. I asked GPT4 to write an example for me, it obliged:

import torch

def LBS(vertices, pose, J, weights):

"""

Linear Blend Skinning (LBS) for the SMPL model.

:param vertices: (N, 6890, 3) tensor of rest pose vertices

:param pose: (N, 24, 3) tensor of relative joint rotations (axis-angle representation)

:param J: (N, 24, 3) tensor of joint locations

:param weights: (6890, 24) tensor of vertex skinning weights

:return: (N, 6890, 3) tensor of skinned vertices

"""

# Convert axis-angle rotations to rotation matrices

rot_mats = torch.zeros((pose.shape[0], 24, 3, 3), device=pose.device)

for i in range(24):

rot_mats[:, i] = axis_angle_to_rotation_matrix(pose[:, i])

# Calculate the local transformations for each joint

local_transforms = rot_mats.clone()

local_transforms[:, :, :3, 2] = J

# Calculate the global transformations for each joint

global_transforms = torch.zeros_like(local_transforms)

global_transforms[:, 0] = local_transforms[:, 0]

for i, parent in enumerate(SMPL_PARENTS[1:], 1):

global_transforms[:, i] = torch.matmul(global_transforms[:, parent], local_transforms[:, i])

# Perform LBS

T = global_transforms[:, :, :3, 2] # Translation part

R = global_transforms[:, :, :3, :3] # Rotation part

skinned_vertices = torch.einsum('biv,bv->bi', (vertices - J), weights) # Subtract joint positions

skinned_vertices = torch.einsum('bij,bijv->biv', R, skinned_vertices[:, None]) # Apply rotations

skinned_vertices = torch.einsum('biv,bv->bi', skinned_vertices, weights) # Blend based on weights

skinned_vertices += torch.einsum('biv,bv->bi', T, weights) # Add translations

return skinned_vertices

Takeaways

In this small post, we focus more on the basics of SMPL, especially in terms of LBS and animation. Obviously, SMPL’s LBS-based approach can not be used in articulated human animation, not to mention detailed rendering. But, because of the flexible parameterization, it is extremely convenient to estimate 2 very small vectors $\vec{\theta}$ , $\vec{\beta}$, and another global $SE(3)$ transformation at most. The tools such as EasyMocap has already made it basically a click-and-run, and it could run very fast (approximately 10-20s, without estimating face and hands keypoints).

The main takeaways I think are:

- SMPL’s blend shape is different than that in 3D softwares such as Maya, Blender, etc. But they are similar in the sense that they all are mixing many different predefined shapes together.

- Parameterize the relative rotation, instead of the absolute 3D joint locations, are actually more robust.

- For rendering. If you are using a volumetric representation, you might need a weights field for the whole 3D scene, because you have to sample points everywhere. If you are using surface rendering, with surface tracing or what not, it is still quite difficult to align the weight with just the surface. As a matter of fact, papers like Snarf also estimates a whole field of weights. I guess this pattern is certainly possible, as proved by many papers already, I do think it is quite ill-posed. If we can find some other parameterization methods, to have a better way to link skinning weights and the geometry, things would be a lot more easier.

Also, as I was writing this post, I came across another blog by Mr. Khanh Ha, which I think is well-written.